05 May | 2020

"Having to communicate the bad news over the phone makes the emotional situation much more difficult"

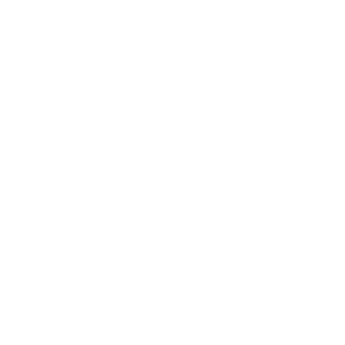

José María González de Echavarri dressed in the individual protection equipment

Dr. José María González de Echavarri, neurologist and member of the Clinical Research, Biomarkers and Risk Factors group of the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center (BBRC), research center of the Pasqual Maragall Foundation, has left in second plan for more than a month his work as a researcher to dedicate himself to caring for patients in one of the COVID-19 plants of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in Barcelona.

Why did you start working at the Hospital de Sant Pau?

To reinforce the hospital's medical staff until the end of May, at least, due to the health crisis caused by the pandemic. As I did my residency there, they called me to work in the new hospital ward of COVID. Until then, I was working full time at the BBRC, but now they have reduced my hours so that I can be full-time in Sant Pau, where we are taking turns doing it to the best of our ability. At first, we started with 12-hour shifts, but now we make them more normal, 8 or 9-hour shifts, and guard duty. It seems that the situation is gradually returning to normal, and hopefully soon, if all goes well, we can see patients with other pathologies in the hospital again, and return to research.

How has your experience been this month in the front line of care for patients with COVID-19?

At the beginning we attended more young people, there were many patients in the ICU. ICU beds had to be increased from 36 to practically more than 100. The initial situation was quite critical. There were very few protective equipment, sometimes we had to reuse masks, you never knew which room you were going to work in ... Then the situation has improved a bit. Now it has become quite noticeable that there are far fewer people admitted, that there are more ICU beds free, and that the hospital is trying to return to normal.

However, on the other hand, we have noticed that in the last few weeks there are more patients derived from nursing homes. These patients are always more fragile and involve more delicate situations and, of course, much higher mortality. Right now, although the situation is better, there are still many patients, and we are receiving the young people who are leaving the ICU. Unfortunately, many of these young people are left with consequences and very long stays at the hospital.

How are you living this situation on a personal level?

There are days that are made hard by fatigue and, above all, by the dramatic situations we live in. On many occasions, there are family members who cannot visit their admitted loved one, who do not know how they are, and we can only speak to them on the phone. This always makes communication difficult. We also find ourselves in very difficult situations when there are patients who are doing poorly or are very fragile, in the situation of the last days or last hours, and their family members are considering whether to go and see him to say goodbye, with the risk that this implies, taking into account that in many cases it is recommended that they do not go because they are older. There are many people who cannot say good-bye. And managing all these kinds of emotions, calling families, is probably the most difficult thing for me, because we are not used to family members not being able to participate in the care of a patient, or having to communicate so much news only on the phone, unable to speak face to face.

It is also true that, in these last few weeks where there have been more nursing home patients, we are seeing much higher mortality. That also makes the job that much harder, as you see patients dying of the coronavirus every day. And having to communicate the bad news over the phone makes the emotional situation much more difficult.

On the other hand, this situation is also hard due to the personal risk that it entails. The teams are limited, and you always work with the stress of not touching, of not contaminating yourself. Just the paraphernalia of dressing in gowns, hats, and masks already makes work harder, making it much more uncomfortable and stressful, especially in situations where a patient is getting worse and you must dress quickly before entering its room. Then you get home, and you have to shower and wash all the clothes. I know it is our job, but somehow it is exhausting to think all the time if we are contaminated or not.

What lessons can we learn from this crisis?

One thing we will probably learn is how important our public health system is, which is stopping the crisis. It is essential that we continue to invest in healthcare, on the one hand, to have the necessary resources and professionals, and in research, on the other.

When we are talking about vaccines, kits, tests, etc., all these kinds of things are supported by research. To the extent that you are better prepared before the blow comes, the better you will receive it. That is, the more you have investigated, and the more you have invested in research before all these things happen, the better you will receive that blow and the sooner you will be able to stop it. In the end, we know that the solution to stop all this is the emergence of a possible vaccine, and much research is required for this.